The optical telegraph, invented in France in 1794, was the fastest means of long-distance communication of its time. It consisted of a chain of towers, each visible from the next, spaced roughly 8 to 12 kilometres apart. At the top of every tower stood a three-metre mast fitted with semaphore arms – three movable beams whose positions formed coded letters. By combining these, operators could transmit words, phrases, and entire sentences across great distances. The system spread swiftly through Europe during the first quarter of the 19th century, soon finding use as far away as America, Algeria, Egypt, and India.

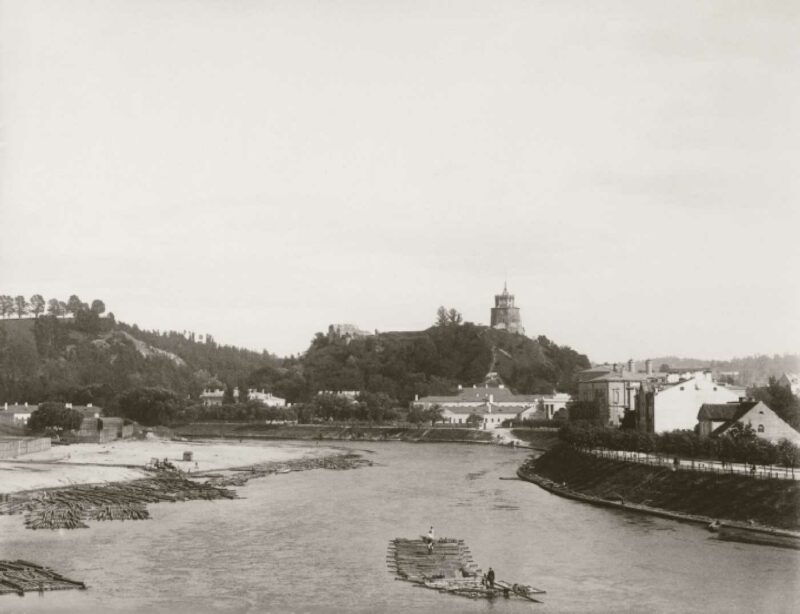

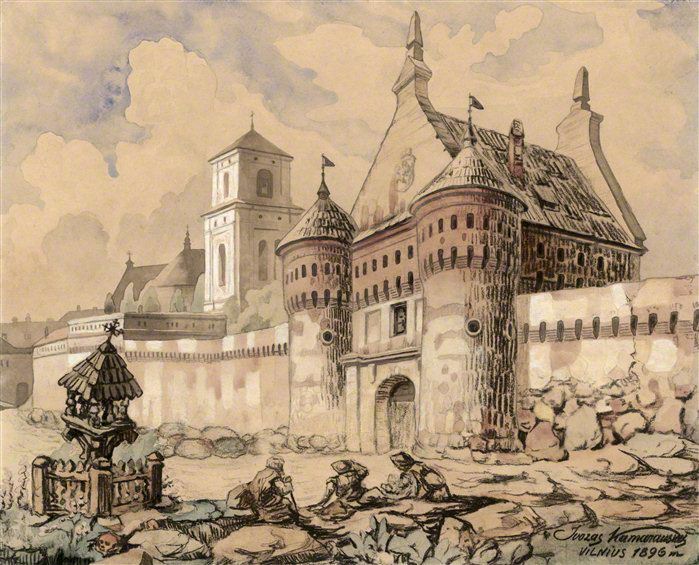

In the summer of 1837, the skyline of Vilnius underwent a dramatic transformation when construction began on a wooden optical telegraph structure atop Gediminas Tower. Inside, the tower was divided into two levels: the lower floor housed an entrance hall and a kitchen for the operators, while the upper level served as their living quarters. The two-storey superstructure, completed in 1838, held the optical telegraph mechanism itself, an observation room, and the director’s office. By the autumn of 1839, the signal operators had moved into the tower.

The St. Petersburg–Warsaw optical telegraph line, operational from 1839 to 1854, was the longest in the world at the time. Stretching over 1,250 kilometres, it employed nearly two thousand people and included 149 stations, 22 of which stood within the Vilnius Governorate. It took as little as 20 minutes for messages to travel from St. Petersburg to Warsaw.

Telegraph operators underwent training at a special school established in 1840. Their task was to reproduce, through a telescope, the exact position of the semaphore arms visible on the nearest tower. They never knew the content of the messages they relayed – only the patterns of movement.

Of course, this invention had its drawbacks: the optical telegraph depended on weather conditions and was visible to anyone curious enough to look. Naturally, the meaning of the secret telegraph codes was known only to a very limited group of people.

The system, for all its ingenuity, was not without flaws. The significant drawbacks of the invention were that its operation depended entirely on clear weather and daylight, and anyone curious enough to look could observe the moving arms from a distance. The meaning of the signals, however, remained known only to a limited circle of trusted officials.

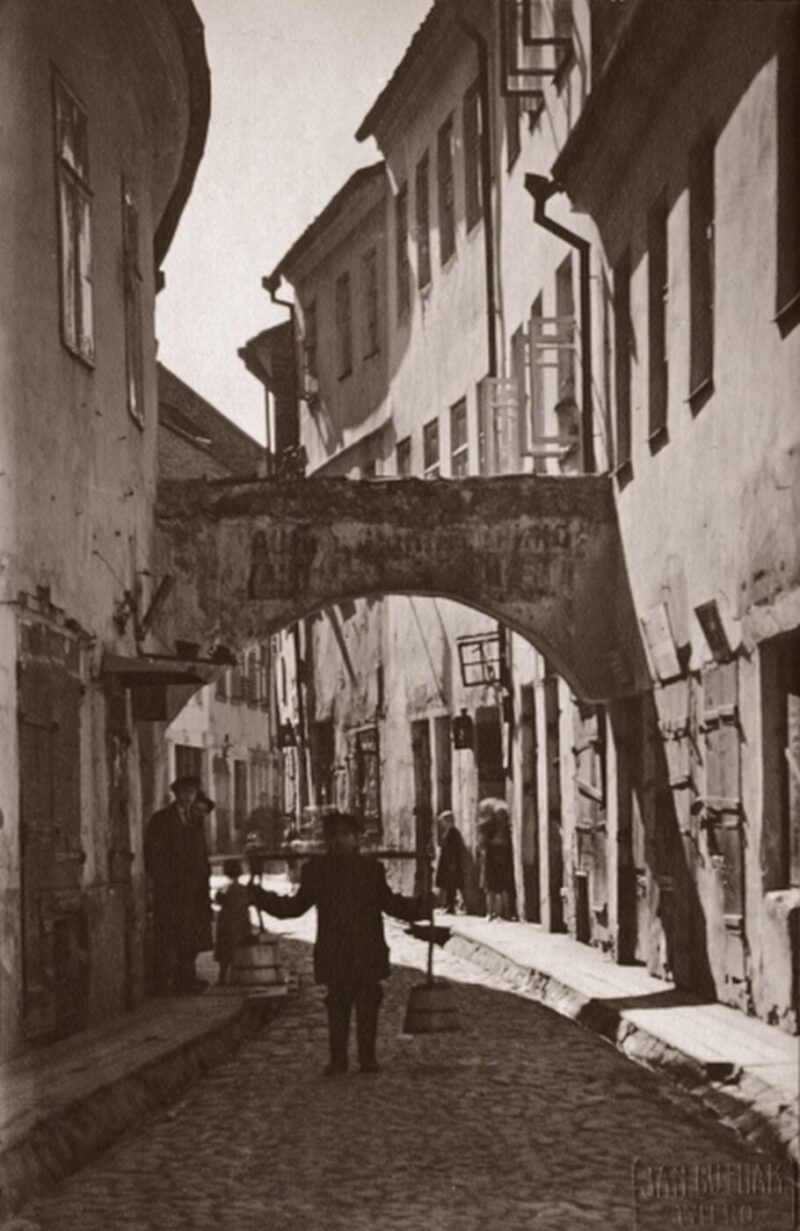

On August 17, 1854, the optical telegraph was finally decommissioned, replaced by the new electromagnetic telegraph line, which marked the beginning of a new era. Soon after, the new telegraph began to be used by government offices, businesses, and newspaper publishers. A few wealthy individuals even had devices installed in their homes. To send a message or greeting, people would go to the post office, dictate the text to a telegraph operator, who would then send it via the device to the specified address. At the other end, an identical device would record the message on a narrow strip of paper, which the clerk would cut and paste onto a sheet or postcard. Then, either the addressee would collect it or a postman would deliver it to their mailbox.

After the Second World War, Vilnius’s city telegraph office operated at Universiteto g. 14. Today, the same building houses a hotel and a restaurant aptly named Telegrafas, which was recognised in the 2024 Michelin Guide.